The Truth Behind the Famous MacArthur Photo

By Joseph Connor

World War II Magazine

December 14, 2016

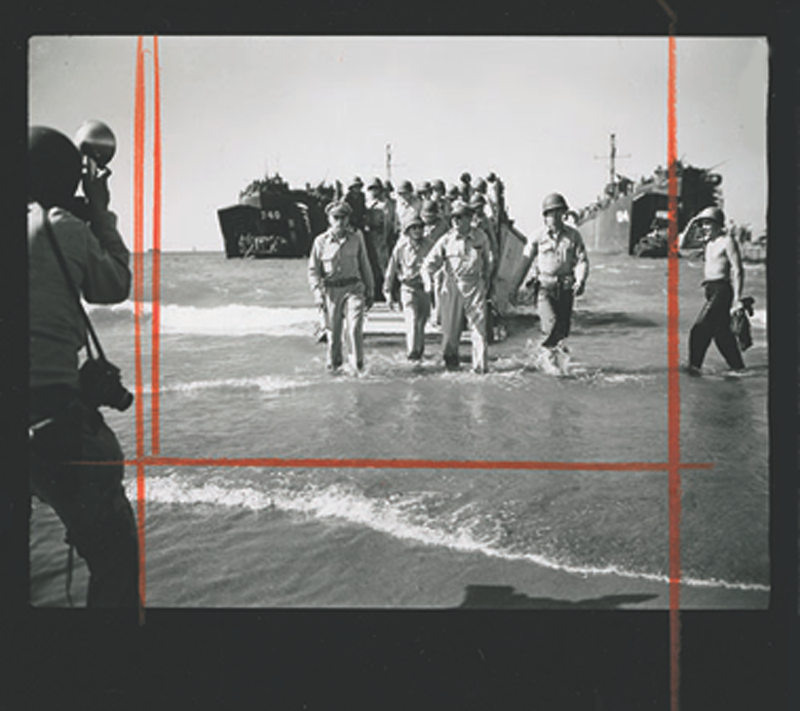

Douglas MacArthur’s anger at being forced to wade ashore at Leyte in October 1944 (above) faded when he saw the powerful photo that resulted.

Iconic photos often have their own stories—some real, some myth

For more than 70 years, questions have swirled around the famous photos of General Douglas MacArthur’s beach landings—first on Leyte, then on Luzon—as American troops returned to liberate the Philippines. Stories persist that MacArthur, no stranger to controversy or drama, staged the photos by coming ashore several times until the cameraman got the perfect shot, or that the photos were posed days after the actual landings. Those who were present say neither of these oft-repeated stories is true. But what really happened is even stranger than these misguided rumors.

MacArthur’s return was the high point of his war. In July 1941 he had been named commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, including all American and Filipino troops in the Philippines. In March 1942, with Japanese forces tightening their grip around the Philippines, MacArthur was ordered out of the islands for Australia. After reaching his destination, he vowed to liberate the Philippines, famously proclaiming, “I shall return.”

By April 1942, Japanese units advancing across the Philippines forced beleaguered Allied troops there to surrender. From then on, the Philippines “constituted the main object of my planning,” MacArthur said. By late 1944 he was poised to fulfill his promise—until an interservice battle threatened to derail his plans.

The U.S. Navy wanted American forces to bypass the Philippines and invade Formosa (now Taiwan) instead. MacArthur objected strenuously, both on strategic grounds and upon his belief that the United States had a moral duty to the people of the Philippines. The dispute went all the way up to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who ultimately sided with MacArthur.

Finally, on October 20, 1944, MacArthur made his long-anticipated return. At 10 a.m., his troops stormed ashore on Leyte, an island in the central Philippines. The heaviest fighting took place on Red Beach, but by early afternoon, MacArthur’s men had secured the area. Secured, however, did not mean safe. Japanese snipers remained active while small-arms and mortar fire continued throughout the day. Hundreds of small landing craft clogged the beaches, but the water was too shallow for larger landing craft to reach dry land.

Aboard the USS Nashville two miles offshore, a restless MacArthur could not wait to put his feet back on Philippine soil. At 1 p.m., he and his staff left the cruiser to take the two-mile landing craft ride to Red Beach. MacArthur intended to step out onto dry land, but soon realized their vessel was too large to advance through the shallow depths near the coastline. An aide radioed the navy beachmaster and asked that a smaller craft be sent to bring them in. The beachmaster, whose word was law on the invasion beach, was too busy with the chaos of the overall invasion to be bothered with a general, no matter how many stars he wore. “Walk in—the water’s fine,” he growled.

The bow of the landing craft dropped and MacArthur and his entourage waded 50 yards through knee-deep water to reach land.

Major Gaetano Faillace, an army photographer assigned to MacArthur, took photos of the general wading ashore. The result was an image of a scowling MacArthur, jaw set firmly, with a steel-eyed look as he approached the beach. But what may have appeared as determination was, in reality, anger. MacArthur was fuming. As he sloshed through the water, he stared daggers at the impudent beachmaster, who had treated the general as he probably had not been treated since his days as a plebe at West Point. However, when MacArthur saw the photo, his anger quickly dissipated. A master at public relations, he knew a good photo when he saw one.

Still, rumors persisted that MacArthur had staged the Leyte photo. CBS radio correspondent William J. Dunn, who was on Red Beach that day, hotly disputed these rumors, calling them “one of the most ludicrous misconceptions to come out of the war.” The photo was “a one-time shot” taken within hours of the initial landing, Dunn said, not something repeated sometime later for the perfect picture. MacArthur biographer D. Clayton James agreed, noting that MacArthur’s “plans for the drama at Red Beach certainly did not include stepping off in knee-deep water.”

The next landing, however, was a different story.

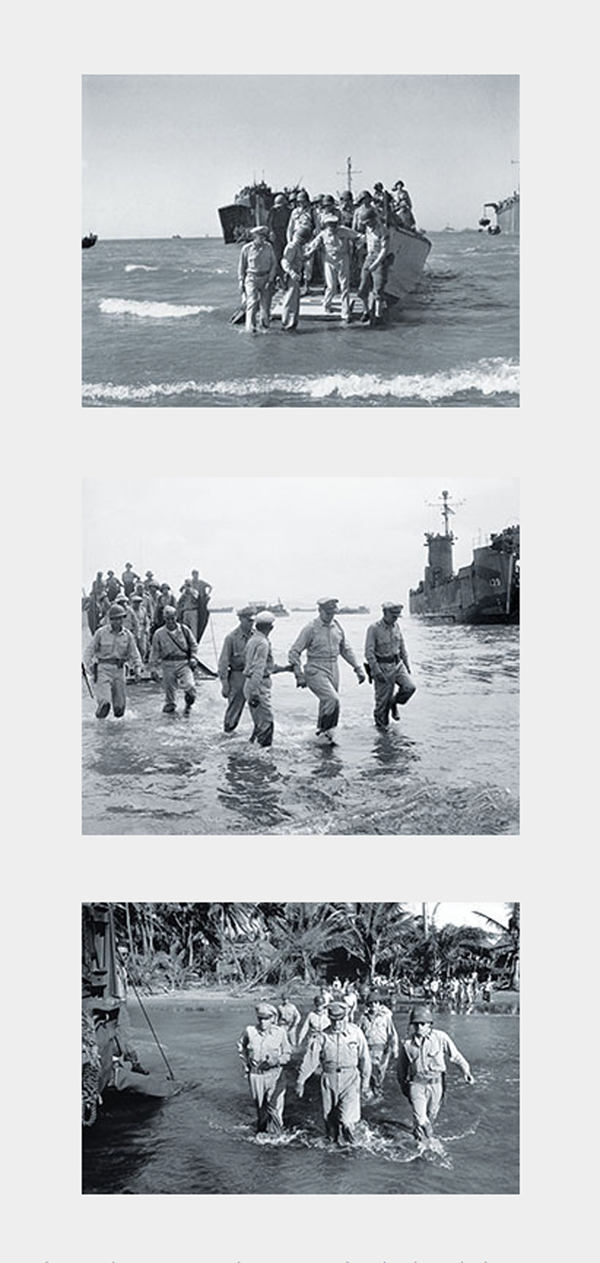

Hoping to replicate the effective walk ashore at Leyte, MacArthur arranged for his landing craft to stop offshore at Luzon, which photographer Carl Mydans captured in this famous image.

On January 9, 1945, American troops arrived at Luzon, the main island in the Philippines, catching the Japanese by surprise. Opposition was light. MacArthur watched the landings from the cruiser USS Boise and at 2 p.m.—about four hours after the initial landings—he headed for shore.

Navy Seabees had quickly built a small pier with pontoons so that MacArthur and his staff could exit their vessel without getting wet. On seeing this, MacArthur ordered his boat to swerve away from the pier so that he could wade ashore through knee-deep water as he had done at Leyte. He knew that Life magazine photographer Carl Mydans was on the beach. As he strode toward shore, MacArthur struck the same pose and steadfast facial expression as at Leyte. Mydans snapped the famous photo that soon appeared on the front pages of newspapers across the United States and became what Time magazine called “an icon of its era.” No one, Mydans said later, appreciated the value of a picture more than MacArthur.

There is little doubt that MacArthur chose to avoid the pier—and dry feet—for dramatic effect. “Having spent a lot of time with MacArthur,” Mydans said, “it flashed on me what was happening. He was avoiding the pontoons.” Biographer D. Clayton James wrote that the Luzon landing “seems to have been a deliberate act of showmanship. With the worldwide attention that his Leyte walk through the water received, apparently the Barrymore side of MacArthur’s personality could not resist another big splash of publicity and surf.”

MacArthur, on the other hand, blamed fate. “As was getting to be a habit with me,” he wrote, perhaps with tongue in cheek, “I picked a boat that took too much draft to reach the beach, and I had to wade in.”

Editors from Life used Maydan’s other photos to present different view of the famous, widely published Luzon photo, perhaps as a ploy to make readers believe they were seeing something different after being scooped.

Other circumstances conspired to make it appear that MacArthur had waded in at Luzon more than once. Although Mydans worked for Life, on that day he was the pool photographer, which gave any news organization free license to use the image. On January 20, 1945, a tightly cropped version of the photo, making MacArthur the focal point, appeared in newspapers throughout the United States. When Life ran the photo a month later, editors used the uncropped version, which included other vessels and figures on the periphery and even another photographer in the foreground. Only a sharp-eyed viewer would realize that it was the photo they had already seen in newspapers weeks earlier, giving rise to the impression of repeat photo sessions. Life had also surrounded the iconic photo with other images Mydans had snapped moments before and after that one, including an unflattering shot of MacArthur being helped down the ramp of the landing craft. All of this may have been a ploy by the magazine—having been scooped by its own photographer—to make readers think they were seeing something new and different.

In the end, controversies about MacArthur’s landings will likely continue. “These are stories that once created will keep being told,” Mydans said, “and each new generation will find…some reason for telling it. Usually it’s with delight.”

Source: HistoryNet.com - This story was originally published in the January/February 2017 issue of World War II magazine